- Home

Page 8

Page 8

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare The Napoleon of Notting Hill

The Napoleon of Notting Hill The Wisdom of Father Brown

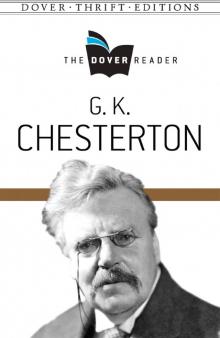

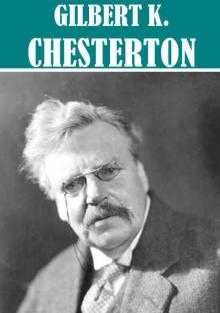

The Wisdom of Father Brown G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader

G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader The Essential G. K. Chesterton

The Essential G. K. Chesterton The Trees of Pride

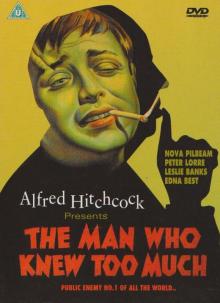

The Trees of Pride The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much The Ball and the Cross

The Ball and the Cross The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed)

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed) The Innocence of Father Brown

The Innocence of Father Brown The Victorian Age in Literature

The Victorian Age in Literature Father Brown Omnibus

Father Brown Omnibus Murder On Christmas Eve

Murder On Christmas Eve The Blue Cross

The Blue Cross The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection What I Saw in America

What I Saw in America