- Home

- G. K. Chesterton

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed)

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed) Read online

G. K. Chesterton

* * *

THE MAN WHO WAS THURSDAY

A Nightmare

Edited with an Introduction by Matthew Beaumont

Contents

Chronology

Introduction

Further Reading

Map

Dedication

1. The Two Poets of Saffron Park

2. The Secret of Gabriel Syme

3. The Man Who Was Thursday

4. The Tale of a Detective

5. The Feast of Fear

6. The Exposure

7. The Unaccountable Conduct of Professor De Worms

8. The Professor Explains

9. The Man in Spectacles

10. The Duel

11. The Criminals Chase the Police

12. The Earth in Anarchy

13. The Pursuit of the President

14. The Six Philosophers

15. The Accuser

Appendix: Extract from an article by G. K. Chesterton

Notes

Follow Penguin

THE MAN WHO WAS THURSDAY

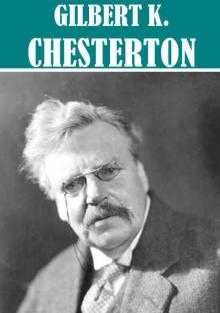

G. K. CHESTERTON was born in 1874, and educated at St Paul’s School, where, despite his efforts to achieve honourable oblivion at the bottom of his class, he was singled out as a boy with distinct literary promise. He decided to follow art as a career, and studied at the Slade School of Art, where he appears to have suffered a nervous breakdown, before turning his hand to journalism, at the suggestion of his friend, Ernest Hodder-Williams. A prolific writer throughout his life, his best-known books include The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1922) and the ‘Father Brown’ stories. Chesterton converted to Roman Catholicism in 1922 and died in 1936.

MATTHEW BEAUMONT is Senior Lecturer in English at University College, London. He is the author of Utopia Ltd.: Ideologies of Social Dreaming in England, 1870-1900, which appeared in paperback in 2009.

Chronology

1874 G.K.C is born on 29 May in Campden Hill, London, to Edward Chesterton, head of a company of house agents and surveyors, and Marie Chesterton.

1879 Birth of Cecil Chesterton, G.K.C’s brother.

1885 Publication of More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter by Robert Louis Stevenson and Fanny van de Grift Stevenson; and The Science of Revolutionary Warfare: A Little Handbook of Instruction in the Use and Preparation of Nitroglycerine, Dynamite, Gun-Cotton, Fulminating Mercury, Bombs, Fuses, Poisons, Etc, Etc. by Johann Most.

1886 Publication of The Princess Casamassima by Henry James; Haymarket Affair, Chicago.

1887 Attends St Paul’s School, London.

1891 Co-founds the Junior Debating Club at St Paul’s.

1892 Publishes ‘The Song of Labour’ in The Speaker; attends University College London.

1893 Attends the Slade School of Art; publication of The Angel of the Revolution by George Griffith.

1896 Publishes ‘A Picture of Tuesday’ in The Quarto.

1900 Publishes Greybeards at Play and The Wild Knight and Other Poems; meets Hilaire Belloc.

1901 Publishes The Defendant and, in The Speaker, ‘A Defence of Patriotism’; contributes for the first time to the Daily News; marries Frances Blogg; moves to Battersea; publication of The Eternal City by Hall Caine.

1902 Publishes Twelve Types, and, with W. Robertson Nicholl, Robert Louis Stevenson; publication of The Wonderful Story of Dunder van Haedan by Edward Chesterton.

1903 Publishes Robert Browning and Varied Types; commences exchange of articles about socialism and Christianity with Robert Blatchford; publication of The Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers, The League of Twelve by Guy Boothby, and A Girl Among the Anarchists by ‘Isabel Meredith’ (Olivia and Helen Rossetti).

1904 Publishes G. F. Watts and The Napoleon of Notting Hill; publication of England: A Nation, edited by Lucian Oldershaw and containing an essay on ‘The Patriotic Idea’ by Chesterton.

1905 Publishes The Club of Queer Trades and Heretics; the British Parliament passes the Aliens Act.

1906 Publishes Charles Dickens; prints ‘The Folly of Anarchists’ in the Illustrated London News.

1907 Publishes ‘The Diabolist’ in the Daily News; appearance of a pilot edition of The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare; publication of The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad.

1908 Publishes The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare, Orthodoxy and All Things Considered; anonymous publication of G. K. Chesterton: A Criticism by Cecil Chesterton; publication of ‘About Chesterton and Belloc’ by H. G. Wells, and ‘Belloc and Chesterton’ by George Bernard Shaw, in the New Age; publication of The Bomb by Frank Harris.

1909 Publishes Tremendous Trifles and George Bernard Shaw; moves to Beaconsfield.

1910 Publishes The Ball and the Cross, William Blake, Alarms and Discussions and What’s Wrong with the World.

1911 Publishes The Innocence of Father Brown, The Future of Religion, The Ballad of the White Horse and Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Dickens; Belloc launches the Eye-Witness (later renamed the New Witness).

1912 Publishes Manalive and A Miscellany of Men.

1913 Publishes The Victorian Age in Literature and Magic; the New Witness, edited by Cecil Chesterton and abetted by G.K.C, is instrumental in exposing the so-called Marconi scandal, centred on allegations that the Liberal government had engaged in insider trading (‘It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-War and Post-War conditions,’ G.K.C wrote in his Autobiography; ‘I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into the Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days’).

1914 Publishes The Flying Inn, The Wisdom of Father Brown, The Barbarism of Berlin, and the privately printed London; suffers physical collapse at Christmas and lapses into a coma from which he recovers at Easter in 1915.

1915 Publishes The Appetite of Tyranny, Including Letters to an Old Garibaldian, Poems and The Crimes of England.

1916 Publishes The Book of Job and A Shilling for My Thoughts; replaces Cecil Chesterton as editor of the New Witness and edits it until 1923.

1917 Publishes A Short History of England, Utopia of Usurers and Other Essays and Lord Kitchener.

1918 Travels to Ireland; death of Cecil Chesterton in France.

1919 Publishes Irish Impressions; prints ‘The Conversion of an Anarchist’ in The Touchstone and The American Art Student Magazine; travels to Palestine.

1920 Publishes The Superstition of Divorce, The Uses of Diversity and The New Jerusalem; travels to the United States to give a lecture tour.

1922 Publishes Eugenics and Other Evils, What I Saw in America and The Man Who Knew Too Much; converts to Roman Catholicism.

1923 Publishes Fancies versus Fads and St Francis of Assisi.

1925 Publishes The Superstitions of the Sceptic, Tales of the Long Bow, The Everlasting Man and William Cobbett; founds G. K.’s Weekly (piloted in 1924).

1926 Publishes The Incredulity of Father Brown, The Outline of Sanity and The Queen of Seven Swords; foundation of the Distributist League.

1927 Publishes The Catholic Church and Conversion, The Return of Don Quixote, Collected Poems, The Secret of Father Brown, The Judgement of Dr Johnson and Robert Louis Stevenson; travels to Poland.

1928 Publishes Generally Speaking, The Sword of Wood and Do We Agree? (based on a debate with Shaw, chaired by Belloc).

1929 Publishes The Poet and the Lunatics, The Thing: Why I am a Catholic and New and Collected Poems; travels to Rome.

1930 Publishes Four Faultless Felons, The Resurrection of Rome, The Grave of Arthur and Come to Think of It; travels to the United States to give a second lecture tour.

1931 Publishes All is Grist.

1932

Publishes Chaucer, New Poems, Sidelights on New London and Newer York and Christendom in Dublin.

1933 Publishes All I Survey and St Thomas Aquinas: The Dumb Ox.

1934 Publishes Avowals and Denials; travels to Italy and Sicily.

1935 Publishes The Scandal of Father Brown, The Well and the Shadows and The Way of the Cross.

1936 Publishes As I Was Saying and Autobiography; dies 14 June at Beaconsfield.

1937 Publication of The Paradoxes of Mr Pond, by G.K.C.

1938 Publication of The Coloured Lands, by G.K.C.

Matthew Beaumont 2011

Introduction

Publisher’s Note: First-time readers should be aware that details of the plot are revealed in this Introduction

The book’s title – comic, no doubt, but at the same time faintly disconcerting – transmits the opening shock. At first, it looks like a typographic mistake. On its publication, in 1908, as Chesterton drily commented in his Autobiography (1936), some reviewers ‘affected to mistake it for “The Man Who Was Thirsty”.’1 If the title initially causes confusion, though, it also inspires a sense of incipient excitement. The Man Who Was … Thursday. The Man isn’t simply called ‘Thursday’, Chesterton implies; he is Thursday. Why? Perhaps he is a remote relation of Thurse, the ancient heathen giant … Perhaps he is the Man Friday of industrial modernity, the archetypal native of the imperial metropolis … Perhaps … The reader’s adventure has already commenced. In the concluding sentence of his Introduction to the old Penguin edition of the book, Kingsley Amis claimed, in characteristically bombastic terms, that anybody who catches sight of its title and ‘does not feel a faint tingle of excitement and a breath of wonder is not really a fit person to be reading the book.’2 It is difficult not to agree. For, in carefully coupling these distinctly prosaic concepts – an anonymous man and an ordinary day of the week – the novel’s title creates a peculiarly poetic effect. In its self-consciously unsettling use of the English language, it touches that sensitive spot which, in Orthodoxy, a spiritual autobiography that also appeared in 1908, Chesterton identified as ‘the nerve of the ancient instinct of astonishment’. It inspires ‘an almost prenatal leap of interest and amazement’.3

Orthodoxy, a book that, characteristically, adopts an attitude both combative and meditative, celebrates what Chesterton describes as ‘a sort of secret treason in the universe’. ‘It is this silent swerving from accuracy by an inch,’ he avers, ‘that is the uncanny element in everything.’4 The title of The Man Who Was Thursday itself swerves from accuracy by an inch. It is thus a potent example of Chesterton’s aspiration, apparent in almost every article or book produced in his exceptionally prolific life, to inspire amazement at that which, perhaps because of some secret treason in the universe, simply happens to be. For Chesterton, whose philosophic outlook in the 1900s was informed by an increasingly profound Christian faith, everyday life was a fabulous, sometimes sinister fairy tale. In this respect, the novel’s title anticipates no other title so much as The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1986), the collection of case histories published to critical and popular acclaim by the psychologist Oliver Sacks. In the chapter that lent Sacks’s book its baffling but strangely beautiful title, he describes a patient of his who ‘saw faces where there were no faces to see’: in the street, this genial man ‘might pat the heads of water-hydrants and parking meters, taking these to be the heads of children; he would amiably address carved knobs on the furniture, and be astounded when they did not reply.’5 Chesterton, whose self-appointed spiritual vocation throughout his life was to irradiate the ordinary, to render it subtly fantastical, might have seen Sacks’s patient as a saint.

If the book’s title recalls a typographical error, then, or a phrase taken from an enigmatic poem, or even a fragment of some singular psychological case history, it also resembles the punchline of a nonsensical joke. ‘The title of Mr G. K. Chesterton’s new story,’ observed the correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, ‘reminds us of the anecdote of an intoxicated man who stopped a policeman in the West-end and asked, “Can you tell me if this is Regent-street – or Wednesday?”’6 Chesterton himself had some respect, as he admitted, for those reviewers who ‘treated it as a mere title out of topsy-turvydom; as if it had been “The Woman Who Was Half Past Eight”, or “The Cow Who Was Tomorrow Evening”.’7 After all, the first book he published, Greybeards at Play (1900), had been a collection of nonsense poems; and in his ‘Defence of Nonsense’ (The Defendent, 1901), he had contended that nonsense is a type of literature absolutely replete with spiritual importance, because it so effectively communicates a sense of amazement at the ‘huge and undecipherable unreason’ of life itself:

Everything has in fact another side to it, like the moon, the patroness of nonsense. Viewed from that other side, a bird is a blossom broken loose from its chain of stalk, a man a quadruped begging on its hind legs, a house a gigantesque hat to cover a man from the sun, a chair an apparatus of four wooden legs for a cripple with only two.8

The title of The Man Who Was Thursday is intended to reveal the other side of the detective novel, the other side of the adventure novel. It defamiliarizes popular forms from the start. Chesterton takes a code that is common to such fiction – Kipling’s ‘The Man Who Would Be King’ (1888) might be one example, Chesterton’s ‘The Man Who Knew Too Much’ (1922) another – and deftly deranges its logic. He deploys the non sequitur, a device the Surrealists subsequently used to such provocative effect, so as to deepen the sense of some almost inscrutable mystery that titles of this kind are intended to evoke. The title is a riddle redoubled.

‘It is no use attempting to say what it is all about,’ wrote Austin Harrison in a review of Chesterton’s novel in the Observer, ‘it is about everything, and that in curiously thrilling detective form.’9 Ostensibly at least, the book is about a battle to the death between anarchists and anti-terrorist detectives in London at the end of the nineteenth century (the ‘boom of bomb throwing’, as Orson Welles so deliciously put it in the comments with which he prefaced his radio adaptation of the novel in 1938).10 It begins in Saffron Park, a bohemian suburb of London, where the protagonist, the respectable young poet Gabriel Syme, encounters another poet, the aesthete and self-professed anarchist Lucien Gregory. After a heated argument about the relationship between politics and aesthetics, one that Gregory hopes to clinch by offering Syme irrefutable proof that he is committed to anarchism, in practice as well as in theory, the former takes the latter to a conspiratorial meeting of dynamitards, located in a subterranean chamber close to the Thames, at which he expects to be elected to one of the seven posts on the Central Anarchist Council. Moments before they enter the chamber, though, after making a pact with Gregory that requires both of them to maintain strict secrecy, Syme reveals that he is actually a police detective:

‘Don’t you see we’ve checkmated each other?’ cried Syme. ‘I can’t tell the police you are an anarchist. You can’t tell the anarchists I’m a policeman. I can only watch you, knowing what you are; you can only watch me, knowing what I am. In short, it’s a lonely, intellectual duel, my head against yours.’ (19)

Then, to Gregory’s deepening horror, in the course of the more and more passionate meeting, the assembled anarchists appoint Syme rather than him to the Council, convinced by this secret agent’s eloquent imitation of an extremist. It is therefore Syme, not Gregory, who subsequently goes to meet the other members of the Council, at a bizarre breakfast party in Leicester Square, where a plan to assassinate both the Russian Czar and the French President is being finalized. These exotic terrorists are all code-named after days of the week; so Syme, who takes up the vacant seat on the Council, becomes Thursday.

The president of the anarchists, a ‘mountain of a man’, as monumental as ‘a statue deliberately carved as colossal’, is Sunday (42). This massive, all-pervasive presence, the spectre haunting Europe, is apparently omnipotent. He is the mastermind, it is increasingly evident, behind the dreamlike events

that ensue, a succession of ominous and at the same time ludicrous social games, conducted at a breakneck pace, involving revelations of concealed identities, violent duels, pitched battles and crazed chases across London and France. In the course of these episodes, in a series of mesmerizing, artfully calculated narrative displacements, it is successively revealed that, like Thursday, each of the anarchists on the Council is in fact a detective in disguise. It finally emerges that Sunday himself is none other than the police chief, who, quite as enigmatic and imposing as the arch-anarchist he has mimicked, has been responsible for recruiting this crack team of anti-terrorists. These disorientating revelations culminate, in the final chapter of the book, in a strange religious ritual, which involves all seven of the anarchists or detectives, who are dressed as the seven days of the Creation, and which is conducted before a vast audience, itself robed in elaborate, dreamlike costumes:

For a long time – it seemed for hours – that huge masquerade of mankind swayed and stamped in front of them to marching and exultant music. Every couple dancing seemed a separate romance; it might be a fairy dancing with a pillar-box, or a peasant girl dancing with the moon; but in each case it was, somehow, as absurd as Alice in Wonderland, yet as grave and kind as a love story. (153)

The people participating in this carnival, to take a formulation from Chesterton’s delightful book on Dickens, ‘have seen the end of the End of the World’.11 The identity of Sunday, however, the mischievous, semi-divine author of this metaphysical farce, remains elusive. Chesterton once intimated that Sunday was not so much God himself, as some commentators had claimed, as ‘Nature as it appears to the pantheist whose pantheism is struggling out of pessimism.’12 But this is at best half-helpful. He seems equally close to the gloriously paganistic image of Christ evoked by Chesterton at the end of Orthodoxy: a ‘tremendous figure’, who ‘never concealed His tears’ and ‘never restrained His anger’, but who nonetheless ‘restrained something’; for ‘there was in that shattering personality a thread that must be called shyness’.13

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare The Napoleon of Notting Hill

The Napoleon of Notting Hill The Wisdom of Father Brown

The Wisdom of Father Brown G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader

G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader The Essential G. K. Chesterton

The Essential G. K. Chesterton The Trees of Pride

The Trees of Pride The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much The Ball and the Cross

The Ball and the Cross The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed)

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed) The Innocence of Father Brown

The Innocence of Father Brown The Victorian Age in Literature

The Victorian Age in Literature Father Brown Omnibus

Father Brown Omnibus Murder On Christmas Eve

Murder On Christmas Eve The Blue Cross

The Blue Cross The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection What I Saw in America

What I Saw in America