- Home

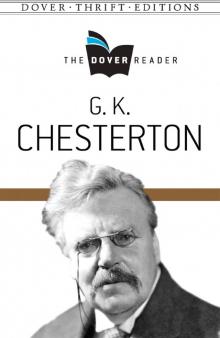

- G. K. Chesterton

The Trees of Pride

The Trees of Pride Read online

Produced by Dianne Bean

THE TREES OF PRIDE

by Gilbert K. Chesterton

THE TREES OF PRIDE:

I. THE TALE OF THE PEACOCK TREES II. THE WAGER OF SQUIRE VANE III. THE MYSTERY OF THE WELL IV. THE CHASE AFTER THE TRUTH

THE TREES OF PRIDE

I. THE TALE OF THE PEACOCK TREES

Squire Vane was an elderly schoolboy of English education and Irishextraction. His English education, at one of the great public schools,had preserved his intellect perfectly and permanently at the stage ofboyhood. But his Irish extraction subconsciously upset in him theproper solemnity of an old boy, and sometimes gave him back the brighteroutlook of a naughty boy. He had a bodily impatience which played tricksupon him almost against his will, and had already rendered him rathertoo radiant a failure in civil and diplomatic service. Thus it is truethat compromise is the key of British policy, especially as effectingan impartiality among the religions of India; but Vane's attempt to meetthe Moslem halfway by kicking off one boot at the gates of the mosque,was felt not so much to indicate true impartiality as something thatcould only be called an aggressive indifference. Again, it is true thatan English aristocrat can hardly enter fully into the feelings of eitherparty in a quarrel between a Russian Jew and an Orthodox processioncarrying relics; but Vane's idea that the procession might carry the Jewas well, himself a venerable and historic relic, was misunderstood onboth sides. In short, he was a man who particularly prided himself onhaving no nonsense about him; with the result that he was always doingnonsensical things. He seemed to be standing on his head merely to provethat he was hard-headed.

He had just finished a hearty breakfast, in the society of his daughter,at a table under a tree in his garden by the Cornish coast. For,having a glorious circulation, he insisted on as many outdoor meals aspossible, though spring had barely touched the woods and warmed theseas round that southern extremity of England. His daughter Barbara, agood-looking girl with heavy red hair and a face as grave as one of thegarden statues, still sat almost motionless as a statue when her fatherrose. A fine tall figure in light clothes, with his white hairand mustache flying backwards rather fiercely from a face that wasgood-humored enough, for he carried his very wide Panama hat in hishand, he strode across the terraced garden, down some stone stepsflanked with old ornamental urns to a more woodland path fringed withlittle trees, and so down a zigzag road which descended the craggy Cliffto the shore, where he was to meet a guest arriving by boat. A yachtwas already in the blue bay, and he could see a boat pulling toward thelittle paved pier.

And yet in that short walk between the green turf and the yellowsands he was destined to find, his hard-headedness provoked into a notunfamiliar phase which the world was inclined to call hot-headedness.The fact was that the Cornish peasantry, who composed his tenantry anddomestic establishment, were far from being people with no nonsenseabout them. There was, alas! a great deal of nonsense about them;with ghosts, witches, and traditions as old as Merlin, they seemed tosurround him with a fairy ring of nonsense. But the magic circle hadone center: there was one point in which the curving conversation of therustics always returned. It was a point that always pricked the Squireto exasperation, and even in this short walk he seemed to strike iteverywhere. He paused before descending the steps from the lawn to speakto the gardener about potting some foreign shrubs, and the gardenerseemed to be gloomily gratified, in every line of his leathery brownvisage, at the chance of indicating that he had formed a low opinion offoreign shrubs.

"We wish you'd get rid of what you've got here, sir," he observed,digging doggedly. "Nothing'll grow right with them here."

"Shrubs!" said the Squire, laughing. "You don't call the peacock treesshrubs, do you? Fine tall trees--you ought to be proud of them."

"Ill weeds grow apace," observed the gardener. "Weeds can grow as houseswhen somebody plants them." Then he added: "Him that sowed tares in theBible, Squire."

"Oh, blast your--" began the Squire, and then replaced the more apt andalliterative word "Bible" by the general word "superstition." He washimself a robust rationalist, but he went to church to set his tenantsan example. Of what, it would have puzzled him to say.

A little way along the lower path by the trees he encountered awoodcutter, one Martin, who was more explicit, having more of agrievance. His daughter was at that time seriously ill with a feverrecently common on that coast, and the Squire, who was a kind-heartedgentleman, would normally have made allowances for low spirits and lossof temper. But he came near to losing his own again when the peasantpersisted in connecting his tragedy with the traditional monomania aboutthe foreign trees.

"If she were well enough I'd move her," said the woodcutter, "as wecan't move them, I suppose. I'd just like to get my chopper into themand feel 'em come crashing down."

"One would think they were dragons," said Vane.

"And that's about what they look like," replied Martin. "Look at 'em!"

The woodman was naturally a rougher and even wilder figure than thegardener. His face also was brown, and looked like an antique parchment,and it was framed in an outlandish arrangement of raven beard andwhiskers, which was really a fashion fifty years ago, but might havebeen five thousand years old or older. Phoenicians, one felt, trading onthose strange shores in the morning of the world, might have combed orcurled or braided their blue-black hair into some such quaint patterns.For this patch of population was as much a corner of Cornwall asCornwall is a corner of England; a tragic and unique race, small andinterrelated like a Celtic clan. The clan was older than the Vanefamily, though that was old as county families go. For in many suchparts of England it is the aristocrats who are the latest arrivals. Itwas the sort of racial type that is supposed to be passing, and perhapshas already passed.

The obnoxious objects stood some hundred yards away from the speaker,who waved toward them with his ax; and there was something suggestive inthe comparison. That coast, to begin with, stretching toward the sunset,was itself almost as fantastic as a sunset cloud. It was cut out againstthe emerald or indigo of the sea in graven horns and crescents thatmight be the cast or mold of some such crested serpents; and, beneath,was pierced and fretted by caves and crevices, as if by the boring ofsome such titanic worms. Over and above this draconian architecture ofthe earth a veil of gray woods hung thinner like a vapor; woods whichthe witchcraft of the sea had, as usual, both blighted and blown out ofshape. To the right the trees trailed along the sea front in a singleline, each drawn out in thin wild lines like a caricature. At the otherend of their extent they multiplied into a huddle of hunchbacked trees,a wood spreading toward a projecting part of the high coast. It was herethat the sight appeared to which so many eyes and minds seemed to bealmost automatically turning.

Out of the middle of this low, and more or less level wood, rose threeseparate stems that shot up and soared into the sky like a lighthouseout of the waves or a church spire out of the village roofs. They formeda clump of three columns close together, which might well be the merebifurcation, or rather trifurcation, of one tree, the lower part beinglost or sunken in the thick wood around. Everything about them suggestedsomething stranger and more southern than anything even in that lastpeninsula of Britain which pushes out farthest toward Spain and Africaand the southern stars. Their leathery leafage had sprouted in advanceof the faint mist of yellow-green around them, and it was of another andless natural green, tinged with blue, like the colors of a kingfisher.But one might fancy it the scales of some three-headed dragon toweringover a herd of huddled and fleeing cattle.

"I am exceedingly sorry your girl is so unwell," said Vane shortly. "Butreally--" and he strode down the steep road with plunging strides.

The boat was already secured to the

little stone jetty, and the boatman,a younger shadow of the woodcutter--and, indeed, a nephew of that usefulmalcontent--saluted his territorial lord with the sullen formality ofthe family. The Squire acknowledged it casually and had soon forgottenall such things in shaking hands with the visitor who had just comeashore. The visitor was a long, loose man, very lean to be so young,whose long, fine features seemed wholly fitted together of bone andnerve, and seemed somehow to contrast with his hair, that showed invivid yellow patches upon his hollow temples under the brim of his whiteholiday hat. He was carefully dressed in exquisite taste, though he hadcome straight from a considerable sea voyage; and he carried somethingin his hand which in his long European travels, and even longer Europeanvisits, he had almost forgotten to call a gripsack.

Mr. Cyprian Paynter was an American who lived in Italy. There was

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare The Napoleon of Notting Hill

The Napoleon of Notting Hill The Wisdom of Father Brown

The Wisdom of Father Brown G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader

G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader The Essential G. K. Chesterton

The Essential G. K. Chesterton The Trees of Pride

The Trees of Pride The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much The Ball and the Cross

The Ball and the Cross The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed)

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed) The Innocence of Father Brown

The Innocence of Father Brown The Victorian Age in Literature

The Victorian Age in Literature Father Brown Omnibus

Father Brown Omnibus Murder On Christmas Eve

Murder On Christmas Eve The Blue Cross

The Blue Cross The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection What I Saw in America

What I Saw in America