- Home

- G. K. Chesterton

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection Page 52

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection Read online

Page 52

‘Pretty elaborate protection, I know,’ said Wain. ‘Maybe it makes you smile a little, Father Brown, to find Merton has to live in a fortress like this without even a tree in the garden for anyone to hide behind. But you don’t know what sort of proposition we’re up against in this country. And perhaps you don’t know just what the name of Brander Merton means. He’s a quiet-looking man enough, and anybody might pass him in the street; not that they get much chance nowadays, for he can only go out now and then in a closed car. But if anything happened to Brander Merton there’d be earthquakes from Alaska to the Cannibal Islands. I fancy there was never a king or emperor who had such power over the nations as he has. After all, I suppose if you’d been asked to visit the tsar, or the king of England, you’d have had the curiosity to go. You mayn’t care much for tsars or millionaires; but it just means that power like that is always interesting. And I hope it’s not against your principles to visit a modern sort of emperor like Merton.’

‘Not at all,’ said Father Brown, quietly. ‘It is my duty to visit prisoners and all miserable men in captivity.’

There was a silence, and the young man frowned with a strange and almost shifty look on his lean face. Then he said, abruptly:

‘Well, you’ve got to remember it isn’t only common crooks or the Black Hand that’s against him. This Daniel Doom is pretty much like the devil. Look how he dropped Trant in his own gardens and Horder outside his house, and got away with it.’

The top floor of the mansion, inside the enormously thick walls, consisted of two rooms; an outer room which they entered, and an inner room that was the great millionaire’s sanctum. They entered the outer room just as two other visitors were coming out of the inner one. One was hailed by Peter Wain as his uncle — a small but very stalwart and active man with a shaven head that looked bald, and a brown face that looked almost too brown to have ever been white. This was old Crake, commonly called Hickory Crake in reminiscence of the more famous Old Hickory, because of his fame in the last Red Indian wars. His companion was a singular contrast — a very dapper gentleman with dark hair like a black varnish and a broad, black ribbon to his monocle: Barnard Blake, who was old Merton’s lawyer and had been discussing with the partners the business of the firm. The four men met in the middle of the outer room and paused for a little polite conversation, in the act of respectively going and coming. And through all goings and comings another figure sat at the back of the room near the inner door, massive and motionless in the half-light from the inner window; a man with a Negro face and enormous shoulders. This was what the humorous self-criticism of America playfully calls the Bad Man; whom his friends might call a bodyguard and his enemies a bravo.

This man never moved or stirred to greet anybody; but the sight of him in the outer room seemed to move Peter Wain to his first nervous query.

‘Is anybody with the chief?’ he asked.

‘Don’t get rattled, Peter,’ chuckled his uncle. ‘Wilton the secretary is with him, and I hope that’s enough for anybody. I don’t believe Wilton ever sleeps for watching Merton. He is better than twenty bodyguards. And he’s quick and quiet as an Indian.’

‘Well, you ought to know,’ said his nephew, laughing. ‘I remember the Red Indian tricks you used to teach me when I was a boy and liked to read Red Indian stories. But in my Red Indian stories Red Indians seemed always to have the worst of it.’

‘They didn’t in real life,’ said the old frontiersman grimly.

‘Indeed?’ inquired the bland Mr Blake. ‘I should have thought they could do very little against our firearms.’

‘I’ve seen an Indian stand under a hundred guns with nothing but a little scalping-knife and kill a white man standing on the top of a fort,’ said Crake.

‘Why, what did he do with it?’ asked the other.

‘Threw it,’ replied Crake, ‘threw it in a flash before a shot could be fired. I don’t know where he learnt the trick.’

‘Well, I hope you didn’t learn it,’ said his nephew, laughing.

‘It seems to me,’ said Father Brown, thoughtfully, ‘that the story might have a moral.’

While they were speaking Mr Wilton, the secretary, had come out of the inner room and stood waiting; a pale, fair-haired man with a square chin and steady eyes with a look like a dog’s; it was not difficult to believe that he had the single — eye of a watchdog.

He only said, ‘Mr Merton can see you in about ten minutes,’ but it served for a signal to break up the gossiping group. Old Crake said he must be off, and his nephew went out with him and his legal companion, leaving Father Brown for the moment alone with his secretary; for the negroid giant at the other end of the room could hardly be felt as if he were human or alive; he sat so motionless with his broad back to them, staring towards the inner room.

‘Arrangements rather elaborate here, I’m afraid,’ said the secretary. ‘You’ve probably heard all about this Daniel Doom, and why it isn’t safe to leave the boss very much alone.’

‘But he is alone just now, isn’t he?’ said Father Brown.

The secretary looked at him with grave, grey eyes. ‘For fifteen minutes,’ he said. ‘For fifteen minutes out of the twenty-four hours. That is all the real solitude he has; and that he insists on, for a pretty remarkable reason.’

‘And what is the reason?’ inquired the visitor. Wilton, the secretary, continued his steady gaze, but his mouth, that had been merely grave, became grim.

‘The Coptic Cup,’ he said. ‘Perhaps you’ve forgotten the Coptic Cup; but he hasn’t forgotten that or anything else. He doesn’t trust any of us about the Coptic Cup. It’s locked up somewhere and somehow in that room so that only he can find it; and he won’t take it out till we’re all out of the way. So we have to risk that quarter of an hour while he sits and worships it; I reckon it’s the only worshipping he does. Not that there’s any risk really; for I’ve turned all this place into a trap I don’t believe the devil himself could get into — or at any rate, get out of. If this infernal Daniel Doom pays us a visit, he’ll stay to dinner and a good bit later, by God! I sit here on hot bricks for the fifteen minutes, and the instant I heard a shot or a sound of struggle I’d press this button and an electrocuting current would run in a ring round that garden wall, so that it ‘ud be death to cross or climb it. Of course, there couldn’t be a shot, for this is the only way in; and the only window he sits at is away up on the top of a tower as smooth as a greasy pole. But, anyhow, we’re all armed here, of course; and if Doom did get into that room he’d be dead before he got out.’

Father Brown was blinking at the carpet in a brown study. Then he said suddenly, with something like a jerk: ‘I hope you won’t mind my mentioning it, but a kind of a notion came into my head just this minute. It’s about you.’

‘Indeed,’ remarked Wilton, ‘and what about me?’

‘I think you are a man of one idea,’ said Father Brown, ‘and you will forgive me for saying that it seems to be even more the idea of catching Daniel Doom than of defending Brander Merton.’

Wilton started a little and continued to stare at his companion; then very slowly his grim mouth took on a rather curious smile. ‘How did you — what makes you think that?’ he asked.

‘You said that if you heard a shot you could instantly electrocute the escaping enemy,’ remarked the priest. ‘I suppose it occurred to you that the shot might be fatal to your employer before the shock was fatal to his foe. I don’t mean that you wouldn’t protect Mr Merton if you could, but it seems to come rather second in your thoughts. The arrangements are very elaborate, as you say, and you seem to have elaborated them. But they seem even more designed to catch a murderer than to save a man.’

‘Father Brown,’ said the secretary, who had recovered his quiet tone, ‘you’re very smart, but there’s something more to you than smartness. Somehow you’re the sort of man to whom one wants to tell the truth; and besides, you’ll probably hear it, anyhow, for in one way it’s a joke against me alre

ady. They all say I’m a monomaniac about running down this big crook, and perhaps I am. But I’ll tell you one thing that none of them know. My full name is John Wilton Border.’ Father Brown nodded as if he were completely enlightened, but the other went on.

‘This fellow who calls himself Doom killed my father and uncle and ruined my mother. When Merton wanted a secretary I took the job, because I thought that where the cup was the criminal might sooner or later be. But I didn’t know who the criminal was and could only wait for him; and I meant to serve Merton faithfully.’

‘I understand,’ said Father Brown gently; ‘and, by the way, isn’t it time that we attended on him?’

‘Why, yes,’ answered Wilton, again starting a little out of his brooding so that the priest concluded that his vindictive mania had again absorbed him for a moment. ‘Go in now by all means.’

Father Brown walked straight into the inner room. No sound of greetings followed, but only a dead silence; and a moment after the priest reappeared in the doorway.

At the same moment the silent bodyguard sitting near the door moved suddenly; and it was as if a huge piece of furniture had come to life. It seemed as though something in the very attitude of the priest had been a signal; for his head was against the light from the inner window and his face was in shadow.

‘I suppose you will press that button,’ he said with a sort of sigh.

Wilton seemed to awake from his savage brooding with a bound and leapt up with a catch in his voice.

‘There was no shot,’ he cried.

‘Well,’ said Father Brown, ‘it depends what you mean by a shot.’

Wilton rushed forward, and they plunged into the inner room together. It was a comparatively small room and simply though elegantly furnished. Opposite to them one wide window stood open, over-looking the garden and the wooded plain. Close up against the window stood a chair and a small table, as if the captive desired as much air and light as was allowed him during his brief luxury of loneliness.

On the little table under the window stood the Coptic Cup; its owner had evidently been looking at it in the best light. It was well worth looking at, for that white and brilliant daylight turned its precious stones to many-coloured flames so that it might have been a model of the Holy Grail. It was well worth looking at; but Brander Merton was not looking at it. For his head had fallen back over his chair, his mane of white hair hanging towards the floor, and his spike of grizzled beard thrust up towards the ceiling, and out of his throat stood a long, brown painted arrow with red feathers at the other end.

‘A silent shot,’ said Father Brown, in a low voice; ‘I was just wondering about those new inventions for silencing firearms. But this is a very old invention, and quite as silent.’

Then, after a moment, he added: ‘I’m afraid he is dead. What are you going to do?’

The pale secretary roused himself with abrupt resolution. ‘I’m going to press that button, of course,’ he said, ‘and if that doesn’t do for Daniel Doom, I’m going to hunt him through the world till I find him.’

‘Take care it doesn’t do for any of our friends,’ observed Father Brown; ‘they can hardly be far off; we’d better call them.’

‘That lot know all about the wall,’ answered Wilton. ‘None of them will try to climb it, unless one of them ... is in a great hurry.’

Father Brown went to the window by which the arrow had evidently entered and looked out. The garden, with its flat flower-beds, lay far below like a delicately coloured map of the world. The whole vista seemed so vast and empty, the tower seemed set so far up in the sky that as he stared out a strange phrase came back to his memory.

‘A bolt from the blue,’ he said. ‘What was that somebody said about a bolt from the blue and death coming out of the sky? Look how far away everything looks; it seems extraordinary that an arrow could come so far, unless it were an arrow from heaven.’

Wilton had returned, but did not reply, and the priest went on as in soliloquy. ‘One thinks of aviation. We must ask young Wain ... about aviation.’

‘There’s a lot of it round here,’ said the secretary.

‘Case of very old or very new weapons,’ observed Father Brown. ‘Some would be quite familiar to his old uncle, I suppose; we must ask him about arrows. This looks rather like a Red Indian arrow. I don’t know where the Red Indian shot it from; but you remember the story the old man told. I said it had a moral.’

‘If it had a moral,’ said Wilton warmly, ‘it was only that a real Red Indian might shoot a thing farther than you’d fancy. It’s nonsense your suggesting a parallel.’

‘I don’t think you’ve got the moral quite right,’ said Father Brown.

Although the little priest appeared to melt into the millions of New York next day, without any apparent attempt to be anything but a number in a numbered street, he was, in fact, unobtrusively busy for the next fortnight with the commission that had been given him, for he was filled with profound fear about a possible miscarriage of justice. Without having any particular air of singling them out from his other new acquaintances, he found it easy to fall into talk with the two or three men recently involved in the mystery; and with old Hickory Crake especially he had a curious and interesting conversation. It took place on a seat in Central Park, where the veteran sat with his bony hands and hatchet face resting on the oddly-shaped head of a walking-stick of dark red wood, possibly modelled on a tomahawk.

‘Well, it may be a long shot,’ he said, wagging his head, ‘but I wouldn’t advise you to be too positive about how far an Indian arrow could go. I’ve known some bow-shots that seemed to go straighter than any bullets, and hit the mark to amazement, considering how long they had been travelling. Of course, you practically never hear now of a Red Indian with a bow and arrows, still less of a Red Indian hanging about here. But if by any chance there were one of the old Indian marksmen, with one of the old Indian bows, hiding in those trees hundreds of yards beyond the Merton outer wall — why, then I wouldn’t put it past the noble savage to be able to send an arrow over the wall and into the top window of Merton’s house; no, nor into Merton, either. I’ve seen things quite as wonderful as that done in the old days.’

‘No doubt,’ said the priest, ‘you have done things quite as wonderful, as well as seen them.’

Old Crake chuckled, and then said gruffly: ‘Oh, that’s all ancient history.’

‘Some people have a way of studying ancient history,’ the priest said. ‘I suppose we may take it there is nothing in your old record to make people talk unpleasantly about this affair.’

‘What do you mean?’ demanded Crake, his eyes shifting sharply for the first time, in his red, wooden face, that was rather like the head of a tomahawk.

‘Well, since you were so well acquainted with all the arts and crafts of the Redskin — ’ began Father Brown slowly.

Crake had had a hunched and almost shrunken appearance as he sat with his chin propped on its queer-shaped crutch. But the next instant he stood erect in the path like a fighting bravo with the crutch clutched like a cudgel.

‘What?’ he cried — in something like a raucous screech — ‘what the hell! Are you standing up to me to tell me I might happen to have murdered my own brother-in-law?’

From a dozen seats dotted about the path people looked to-wards the disputants, as they stood facing each other in the middle of the path, the bald-headed energetic little man brandishing his outlandish stick like a club, and the black, dumpy figure of the little cleric looking at him without moving a muscle, save for his hinging eyelids. For a moment it looked as if the black, dumpy figure would be knocked on the head, and laid out with true Red Indian promptitude and dispatch; and the large form of an Irish policeman could be seen heaving up in the distance and bearing down on the group. But the priest only said, quite placidly, like one answering an ordinary query:

‘I have formed certain conclusions about it, but I do not think I will mention them till I make my report.’

‘It’s a wonder you didn’t see any while we were there,’ answered Captain Wain. ‘Sometimes they’re as thick as flies; that open plain is a great place for them, and I shouldn’t wonder if it were the chief breeding-ground, so to speak, for my sort of birds in the future. I’ve flown a good deal there myself, of course, and I know most of the fellows about here who flew in the war; but there are a whole lot of people taking to it out there now whom I never heard of in my life. I suppose it will be like motoring soon, and every man in the States will have one.’

‘Being endowed by his Creator,’ said Father Brown with a smile, ’with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of motoring — not to mention aviation. So I suppose we may take it that one strange aeroplane passing over that house, at certain times, wouldn’t be noticed much.’

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare The Napoleon of Notting Hill

The Napoleon of Notting Hill The Wisdom of Father Brown

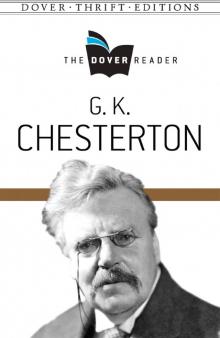

The Wisdom of Father Brown G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader

G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader The Essential G. K. Chesterton

The Essential G. K. Chesterton The Trees of Pride

The Trees of Pride The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much The Ball and the Cross

The Ball and the Cross The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed)

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed) The Innocence of Father Brown

The Innocence of Father Brown The Victorian Age in Literature

The Victorian Age in Literature Father Brown Omnibus

Father Brown Omnibus Murder On Christmas Eve

Murder On Christmas Eve The Blue Cross

The Blue Cross The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection What I Saw in America

What I Saw in America