- Home

- G. K. Chesterton

The Ball and the Cross Page 4

The Ball and the Cross Read online

Page 4

IV. A DISCUSSION AT DAWN

The duellists had from their own point of view escaped or conquered thechief powers of the modern world. They had satisfied the magistrate,they had tied the tradesman neck and heels, and they had left thepolice behind. As far as their own feelings went they had melted into amonstrous sea; they were but the fare and driver of one of the millionhansoms that fill London streets. But they had forgotten something; theyhad forgotten journalism. They had forgotten that there exists in themodern world, perhaps for the first time in history, a class of peoplewhose interest is not that things should happen well or happen badly,should happen successfully or happen unsuccessfully, should happen tothe advantage of this party or the advantage of that part, but whoseinterest simply is that things should happen.

It is the one great weakness of journalism as a picture of our modernexistence, that it must be a picture made up entirely of exceptions. Weannounce on flaring posters that a man has fallen off a scaffolding.We do not announce on flaring posters that a man has not fallen off ascaffolding. Yet this latter fact is fundamentally more exciting, asindicating that that moving tower of terror and mystery, a man, is stillabroad upon the earth. That the man has not fallen off a scaffolding isreally more sensational; and it is also some thousand times more common.But journalism cannot reasonably be expected thus to insist upon thepermanent miracles. Busy editors cannot be expected to put on theirposters, "Mr. Wilkinson Still Safe," or "Mr. Jones, of Worthing, NotDead Yet." They cannot announce the happiness of mankind at all. Theycannot describe all the forks that are not stolen, or all the marriagesthat are not judiciously dissolved. Hence the complete picture theygive of life is of necessity fallacious; they can only represent whatis unusual. However democratic they may be, they are only concerned withthe minority.

The incident of the religious fanatic who broke a window on Ludgate Hillwas alone enough to set them up in good copy for the night. But when thesame man was brought before a magistrate and defied his enemy tomortal combat in the open court, then the columns would hardly hold theexcruciating information, and the headlines were so large that there washardly room for any of the text. The _Daily Telegraph_ headed a column,"A Duel on Divinity," and there was a correspondence afterwards whichlasted for months, about whether police magistrates ought to mentionreligion. The _Daily Mail_ in its dull, sensible way, headed the events,"Wanted to fight for the Virgin." Mr. James Douglas, in _The Star_,presuming on his knowledge of philosophical and theological terms,described the Christian's outbreak under the title of "Dualist andDuellist." The _Daily News_ inserted a colourless account of the matter,but was pursued and eaten up for some weeks, with letters from outlyingministers, headed "Murder and Mariolatry." But the journalistictemperature was steadily and consistently heated by all theseinfluences; the journalists had tasted blood, prospectively, and werein the mood for more; everything in the matter prepared them for furtheroutbursts of moral indignation. And when a gasping reporter rushed in inthe last hours of the evening with the announcement that the two heroesof the Police Court had literally been found fighting in a London backgarden, with a shopkeeper bound and gagged in the front of the house,the editors and sub-editors were stricken still as men are by greatbeatitudes.

The next morning, five or six of the great London dailies burst outsimultaneously into great blossoms of eloquent leader-writing. Towardsthe end all the leaders tended to be the same, but they all begandifferently. The _Daily Telegraph_, for instance began, "There willbe little difference among our readers or among all truly English andlaw-abiding men touching the, etc. etc." The _Daily Mail_ said, "Peoplemust learn, in the modern world, to keep their theological differencesto themselves. The fracas, etc. etc." The _Daily News_ started, "Nothingcould be more inimical to the cause of true religion than, etc. etc."The _Times_ began with something about Celtic disturbances of theequilibrium of Empire, and the _Daily Express_ distinguished itselfsplendidly by omitting altogether so controversial a matter andsubstituting a leader about goloshes.

And the morning after that, the editors and the newspapers were in sucha state, that, as the phrase is, there was no holding them. Whateversecret and elvish thing it is that broods over editors and suddenlyturns their brains, that thing had seized on the story of the brokenglass and the duel in the garden. It became monstrous and omnipresent,as do in our time the unimportant doings of the sect of theAgapemonites, or as did at an earlier time the dreary dishonestiesof the Rhodesian financiers. Questions were asked about it, and evenanswered, in the House of Commons. The Government was solemnly denouncedin the papers for not having done something, nobody knew what, toprevent the window being broken. An enormous subscription was startedto reimburse Mr. Gordon, the man who had been gagged in the shop. Mr.MacIan, one of the combatants, became for some mysterious reason, singlyand hugely popular as a comic figure in the comic papers and on thestage of the music hall. He was always represented (in defiance offact), with red whiskers, and a very red nose, and in full Highlandcostume. And a song, consisting of an unimaginable number of verses,in which his name was rhymed with flat iron, the British Lion, sly 'un,dandelion, Spion (With Kop in the next line), was sung to crowded housesevery night. The papers developed a devouring thirst for the capture ofthe fugitives; and when they had not been caught for forty-eight hours,they suddenly turned the whole matter into a detective mystery. Lettersunder the heading, "Where are They," poured in to every paper, withevery conceivable kind of explanation, running them to earth in theMonument, the Twopenny Tube, Epping Forest, Westminster Abbey, rolled upin carpets at Shoolbreds, locked up in safes in Chancery Lane. Yes, thepapers were very interesting, and Mr. Turnbull unrolled a whole bundleof them for the amusement of Mr. MacIan as they sat on a high common tothe north of London, in the coming of the white dawn.

The darkness in the east had been broken with a bar of grey; the barof grey was split with a sword of silver and morning lifted itselflaboriously over London. From the spot where Turnbull and MacIan weresitting on one of the barren steeps behind Hampstead, they could seethe whole of London shaping itself vaguely and largely in the grey andgrowing light, until the white sun stood over it and it lay at theirfeet, the splendid monstrosity that it is. Its bewildering squares andparallelograms were compact and perfect as a Chinese puzzle; an enormoushieroglyphic which man must decipher or die. There fell upon both ofthem, but upon Turnbull more than the other, because he know more whatthe scene signified, that quite indescribable sense as of a sublime andpassionate and heart-moving futility, which is never evoked by desertsor dead men or men neglected and barbarous, which can only be invoked bythe sight of the enormous genius of man applied to anything other thanthe best. Turnbull, the old idealistic democrat, had so often reviledthe democracy and reviled them justly for their supineness, theirsnobbishness, their evil reverence for idle things. He was right enough;for our democracy has only one great fault; it is not democratic. Andafter denouncing so justly average modern men for so many years assophists and as slaves, he looked down from an empty slope in Hampsteadand saw what gods they are. Their achievement seemed all the more heroicand divine, because it seemed doubtful whether it was worth doing atall. There seemed to be something greater than mere accuracy in makingsuch a mistake as London. And what was to be the end of it all? what wasto be the ultimate transformation of this common and incredible Londonman, this workman on a tram in Battersea, his clerk on an omnibus inCheapside? Turnbull, as he stared drearily, murmured to himselfthe words of the old atheistic and revolutionary Swinburne who hadintoxicated his youth:

"And still we ask if God or man Can loosen thee Lazarus; Bid thee rise up republican, And save thyself and all of us. But no disciple's tongue can say If thou can'st take our sins away."

Turnbull shivered slightly as if behind the earthly morning he felt theevening of the world, the sunset of so many hopes. Those words were from"Songs before Sunrise". But Turnbull's songs at their best were songsafter sunrise, and sunrise had been no s

uch great thing after all.Turnbull shivered again in the sharp morning air. MacIan was also gazingwith his face towards the city, but there was that about his blind andmystical stare that told one, so to speak, that his eyes were turnedinwards. When Turnbull said something to him about London, they seemedto move as at a summons and come out like two householders coming outinto their doorways.

"Yes," he said, with a sort of stupidity. "It's a very big place."

There was a somewhat unmeaning silence, and then MacIan said again:

"It's a very big place. When I first came into it I was frightened ofit. Frightened exactly as one would be frightened at the sight of aman forty feet high. I am used to big things where I come from, bigmountains that seem to fill God's infinity, and the big sea that goesto the end of the world. But then these things are all shapeless andconfused things, not made in any familiar form. But to see the plain,square, human things as large as that, houses so large and streetsso large, and the town itself so large, was like having screwed somedevil's magnifying glass into one's eye. It was like seeing a porridgebowl as big as a house, or a mouse-trap made to catch elephants."

"Like the land of the Brobdingnagians," said Turnbull, smiling.

"Oh! Where is that?" said MacIan.

Turnbull said bitterly, "In a book," and the silence fell suddenlybetween them again.

They were sitting in a sort of litter on the hillside; all the thingsthey had hurriedly collected, in various places, for their flight, werestrewn indiscriminately round them. The two swords with which they hadlately sought each other's lives were flung down on the grass at random,like two idle walking-sticks. Some provisions they had bought lastnight, at a low public house, in case of undefined contingencies, weretossed about like the materials of an ordinary picnic, here a basketof chocolate, and there a bottle of wine. And to add to the disorderfinally, there were strewn on top of everything, the most disorderlyof modern things, newspapers, and more newspapers, and yet againnewspapers, the ministers of the modern anarchy. Turnbull picked up oneof them drearily, and took out a pipe.

"There's a lot about us," he said. "Do you mind if I light up?"

"Why should I mind?" asked MacIan.

Turnbull eyed with a certain studious interest, the man who did notunderstand any of the verbal courtesies; he lit his pipe and blew greatclouds out of it.

"Yes," he resumed. "The matter on which you and I are engaged is at thismoment really the best copy in England. I am a journalist, and I know.For the first time, perhaps, for many generations, the English arereally more angry about a wrong thing done in England than they areabout a wrong thing done in France."

"It is not a wrong thing," said MacIan.

Turnbull laughed. "You seem unable to understand the ordinary use of thehuman language. If I did not suspect that you were a genius, I shouldcertainly know you were a blockhead. I fancy we had better be gettingalong and collecting our baggage."

And he jumped up and began shoving the luggage into his pockets, orstrapping it on to his back. As he thrust a tin of canned meat, anyhow,into his bursting side pocket, he said casually:

"I only meant that you and I are the most prominent people in theEnglish papers."

"Well, what did you expect?" asked MacIan, opening his great grave blueeyes.

"The papers are full of us," said Turnbull, stooping to pick up one ofthe swords.

MacIan stooped and picked up the other.

"Yes," he said, in his simple way. "I have read what they have to say.But they don't seem to understand the point."

"The point of what?" asked Turnbull.

"The point of the sword," said MacIan, violently, and planted the steelpoint in the soil like a man planting a tree.

"That is a point," said Turnbull, grimly, "that we will discuss later.Come along."

Turnbull tied the last tin of biscuits desperately to himself withstring; and then spoke, like a diver girt for plunging, short and sharp.

"Now, Mr. MacIan, you must listen to me. You must listen to me, notmerely because I know the country, which you might learn by looking ata map, but because I know the people of the country, whom you couldnot know by living here thirty years. That infernal city down there isawake; and it is awake against us. All those endless rows of windows andwindows are all eyes staring at us. All those forests of chimneys arefingers pointing at us, as we stand here on the hillside. This thing hascaught on. For the next six mortal months they will think of nothingbut us, as for six mortal months they thought of nothing but the Dreyfuscase. Oh, I know it's funny. They let starving children, who don'twant to die, drop by the score without looking round. But because twogentlemen, from private feelings of delicacy, do want to die, they willmobilize the army and navy to prevent them. For half a year or more, youand I, Mr. MacIan, will be an obstacle to every reform in the BritishEmpire. We shall prevent the Chinese being sent out of the Transvaal andthe blocks being stopped in the Strand. We shall be the conversationalsubstitute when anyone recommends Home Rule, or complains of sky signs.Therefore, do not imagine, in your innocence, that we have only to meltaway among those English hills as a Highland cateran might into yourgod-forsaken Highland mountains. We must be eternally on our guard; wemust live the hunted life of two distinguished criminals. We must expectto be recognized as much as if we were Napoleon escaping from Elba. Wemust be prepared for our descriptions being sent to every tiny village,and for our faces being recognized by every ambitious policeman. Wemust often sleep under the stars as if we were in Africa. Last and mostimportant we must not dream of effecting our--our final settlement,which will be a thing as famous as the Phoenix Park murders, unless wehave made real and precise arrangements for our isolation--I will notsay our safety. We must not, in short, fight until we have thrown themoff our scent, if only for a moment. For, take my word for it, Mr.MacIan, if the British Public once catches us up, the British Publicwill prevent the duel, if it is only by locking us both up in asylumsfor the rest of our days."

MacIan was looking at the horizon with a rather misty look.

"I am not at all surprised," he said, "at the world being against us. Itmakes me feel I was right to----"

"Yes?" said Turnbull.

"To smash your window," said MacIan. "I have woken up the world."

"Very well, then," said Turnbull, stolidly. "Let us look at a fewfinal facts. Beyond that hill there is comparatively clear country.Fortunately, I know the part well, and if you will follow me exactly,and, when necessary, on your stomach, we may be able to get ten milesout of London, literally without meeting anyone at all, which will bethe best possible beginning, at any rate. We have provisions for atleast two days and two nights, three days if we do it carefully. We maybe able to get fifty or sixty miles away without even walking into aninn door. I have the biscuits and the tinned meat, and the milk. Youhave the chocolate, I think? And the brandy?"

"Yes," said MacIan, like a soldier taking orders.

"Very well, then, come on. March. We turn under that third bush and sodown into the valley." And he set off ahead at a swinging walk.

Then he stopped suddenly; for he realized that the other was notfollowing. Evan MacIan was leaning on his sword with a lowering face,like a man suddenly smitten still with doubt.

"What on earth is the matter?" asked Turnbull, staring in some anger.

Evan made no reply.

"What the deuce is the matter with you?" demanded the leader, again, hisface slowly growing as red as his beard; then he said, suddenly, and ina more human voice, "Are you in pain, MacIan?"

"Yes," replied the Highlander, without lifting his face.

"Take some brandy," cried Turnbull, walking forward hurriedly towardshim. "You've got it."

"It's not in the body," said MacIan, in his dull, strange way. "Thepain has come into my mind. A very dreadful thing has just come into mythoughts."

"What the devil are you talking about?" asked Turnbull.

MacIan broke out with a queer and living voice.

"We must

fight now, Turnbull. We must fight now. A frightful thing hascome upon me, and I know it must be now and here. I must kill you here,"he cried, with a sort of tearful rage impossible to describe. "Here,here, upon this blessed grass."

"Why, you idiot," began Turnbull.

"The hour has come--the black hour God meant for it. Quick, it will soonbe gone. Quick!"

And he flung the scabbard from him furiously, and stood with thesunlight sparkling along his sword.

"You confounded fool," repeated Turnbull. "Put that thing up again,you ass; people will come out of that house at the first clash of thesteel."

"One of us will be dead before they come," said the other, hoarsely,"for this is the hour God meant."

"Well, I never thought much of God," said the editor of _The Atheist_,losing all patience. "And I think less now. Never mind what God meant.Kindly enlighten my pagan darkness as to what the devil _you_ mean."

"The hour will soon be gone. In a moment it will be gone," said themadman. "It is now, now, now that I must nail your blaspheming body tothe earth--now, now that I must avenge Our Lady on her vile slanderer.Now or never. For the dreadful thought is in my mind."

"And what thought," asked Turnbull, with frantic composure, "occupieswhat you call your mind?"

"I must kill you now," said the fanatic, "because----"

"Well, because," said Turnbull, patiently.

"Because I have begun to like you."

Turnbull's face had a sudden spasm in the sunlight, a change soinstantaneous that it left no trace behind it; and his features seemedstill carved into a cold stare. But when he spoke again he seemed likea man who was placidly pretending to misunderstand something that heunderstood perfectly well.

"Your affection expresses itself in an abrupt form," he began, butMacIan broke the brittle and frivolous speech to pieces with a violentvoice. "Do not trouble to talk like that," he said. "You know what Imean as well as I know it. Come on and fight, I say. Perhaps you arefeeling just as I do."

Turnbull's face flinched again in the fierce sunlight, but his attitudekept its contemptuous ease.

"Your Celtic mind really goes too fast for me," he said; "let me bepermitted in my heavy Lowland way to understand this new development. Mydear Mr. MacIan, what do you really mean?"

MacIan still kept the shining sword-point towards the other's breast.

"You know what I mean. You mean the same yourself. We must fight now orelse----"

"Or else?" repeated Turnbull, staring at him with an almost blindinggravity.

"Or else we may not want to fight at all," answered Evan, and the end ofhis speech was like a despairing cry.

Turnbull took out his own sword suddenly as if to engage; then plantingit point downwards for a moment, he said, "Before we begin, may I askyou a question?"

MacIan bowed patiently, but with burning eyes.

"You said, just now," continued Turnbull, presently, "that if we did notfight now, we might not want to fight at all. How would you feel aboutthe matter if we came not to want to fight at all?"

"I should feel," answered the other, "just as I should feel if you haddrawn your sword, and I had run away from it. I should feel that becauseI had been weak, justice had not been done."

"Justice," answered Turnbull, with a thoughtful smile, "but we aretalking about your feelings. And what do you mean by justice, apart fromyour feelings?"

MacIan made a gesture of weary recognition! "Oh, Nominalism," he said,with a sort of sigh, "we had all that out in the twelfth century."

"I wish we could have it out now," replied the other, firmly. "Do youreally mean that if you came to think me right, you would be certainlywrong?"

"If I had a blow on the back of my head, I might come to think you agreen elephant," answered MacIan, "but have I not the right to say now,that if I thought that I should think wrong?"

"Then you are quite certain that it would be wrong to like me?" askedTurnbull, with a slight smile.

"No," said Evan, thoughtfully, "I do not say that. It may not be thedevil, it may be some part of God I am not meant to know. But I had awork to do, and it is making the work difficult."

"And I suppose," said the atheist, quite gently, "that you and I knowall about which part of God we ought to know."

MacIan burst out like a man driven back and explaining everything.

"The Church is not a thing like the Athenaeum Club," he cried. "If theAthenaeum Club lost all its members, the Athenaeum Club would dissolveand cease to exist. But when we belong to the Church we belong tosomething which is outside all of us; which is outside everything youtalk about, outside the Cardinals and the Pope. They belong to it, butit does not belong to them. If we all fell dead suddenly, the Churchwould still somehow exist in God. Confound it all, don't you see that Iam more sure of its existence than I am of my own existence? And yet youask me to trust my temperament, my own temperament, which can be turnedupside down by two bottles of claret or an attack of the jaundice. Youask me to trust that when it softens towards you and not to trust thething which I believe to be outside myself and more real than the bloodin my body."

"Stop a moment," said Turnbull, in the same easy tone, "Even in the veryact of saying that you believe this or that, you imply that there is apart of yourself that you trust even if there are many parts which youmistrust. If it is only you that like me, surely, also, it is only youthat believe in the Catholic Church."

Evan remained in an unmoved and grave attitude. "There is a part of mewhich is divine," he answered, "a part that can be trusted, but thereare also affections which are entirely animal and idle."

"And you are quite certain, I suppose," continued Turnbull, "that ifeven you esteem me the esteem would be wholly animal and idle?" For thefirst time MacIan started as if he had not expected the thing that wassaid to him. At last he said:

"Whatever in earth or heaven it is that has joined us two together, itseems to be something which makes it impossible to lie. No, I do notthink that the movement in me towards you was...was that surface sort ofthing. It may have been something deeper...something strange. I cannotunderstand the thing at all. But understand this and understand itthoroughly, if I loved you my love might be divine. No, it is not sometrifle that we are fighting about. It is not some superstition or somesymbol. When you wrote those words about Our Lady, you were in that acta wicked man doing a wicked thing. If I hate you it is because you havehated goodness. And if I like you...it is because you are good."

Turnbull's face wore an indecipherable expression.

"Well, shall we fight now?" he said.

"Yes," said MacIan, with a sudden contraction of his black brows, "yes,it must be now."

The bright swords crossed, and the first touch of them, travellingdown blade and arm, told each combatant that the heart of the other wasawakened. It was not in that way that the swords rang together when theyhad rushed on each other in the little garden behind the dealer's shop.

There was a pause, and then MacIan made a movement as if to thrust,and almost at the same moment Turnbull suddenly and calmly dropped hissword. Evan stared round in an unusual bewilderment, and then realizedthat a large man in pale clothes and a Panama hat was strolling serenelytowards them.

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare The Napoleon of Notting Hill

The Napoleon of Notting Hill The Wisdom of Father Brown

The Wisdom of Father Brown G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader

G K Chesterton- The Dover Reader The Essential G. K. Chesterton

The Essential G. K. Chesterton The Trees of Pride

The Trees of Pride The Man Who Knew Too Much

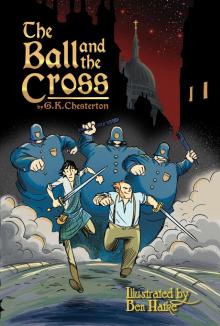

The Man Who Knew Too Much The Ball and the Cross

The Ball and the Cross The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed)

The Man Who Was Thursday (Penguin ed) The Innocence of Father Brown

The Innocence of Father Brown The Victorian Age in Literature

The Victorian Age in Literature Father Brown Omnibus

Father Brown Omnibus Murder On Christmas Eve

Murder On Christmas Eve The Blue Cross

The Blue Cross The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection

The Complete Father Brown Mysteries Collection What I Saw in America

What I Saw in America